What's Really in Your Food? How to Read a Nutritional Label

Navigating the supermarket can be a minefield. That cereal box promising "high fibre" or the energy bar claiming "high protein" might be hiding a less-than-healthy reality.

Food companies are masters of marketing, and they know what buzzwords get our attention. But once you know how to read the Nutritional Information Panel (NIP), you can look past the marketing claims and make choices that genuinely support your health goals.

The key to interpreting a label is to not focus too much on an individual nutrient but to assess the food in the context of the whole product, and then in the context of your whole diet.

Here’s a breakdown of what to look for and what to be mindful of on a nutritional label in New Zealand.

Energy (Calories and Kilojoules)

This is the most fundamental part of a food label. Food is broken down by the body to release energy, which is then used by your cells to grow, repair, and move.

What to Look For: The energy value is listed in kilojoules (kJ) and often includes the kilocalorie (Cal) value in brackets.

The Math: To convert kilojoules to calories, you can divide by 4.2. For example, 1000 kJ is approximately 239 Calories. A difference of 400kJ between products might seem like a lot, but this only equates to roughly 95 Calories.

The Strategy: Understanding the energy value of a food is a crucial part of weight management. If we consistently consume more energy than our body needs, that excess is stored as body fat. However, it's not the only factor. Not all calories are created equal—the type of nutrients in the food matters just as much as the quantity of energy.

The Serving Size

This is the most important—and most misleading—part of the label. All the numbers on the panel are based on a single serving, which is often far smaller than what a person would typically eat.

What to Look For: Pay close attention to the "per serving" and "per 100g" columns.

The Trick: A bag of chips might have a serving size of just 30g, but you're likely to eat the whole bag. If the label says it's "low sugar" per serving, but there are four servings in the bag, you could be consuming a significant amount of sugar.

The Strategy: Always compare the serving size to what you actually consume. The "per 100g" column is your best friend for making fair comparisons between different products.

Whole Foods vs. Processed Foods

Most of the foods you should be eating—like fresh fruit, vegetables, meat, and fish—don’t even have a label! A great rule of thumb is this: if the food is a whole food or unprocessed, don’t worry about checking the label. For these items, simply focus on eating a variety of them.

Carbohydrates & Sugars

Carbohydrates have become a feared nutrient, but they are a vital source of energy. The important thing to remember is to put the type of carbohydrate in context. The carbohydrate listed on the label of a processed product like ice cream is a very different story to the carbohydrate listed on the label of a whole food like rolled oats.

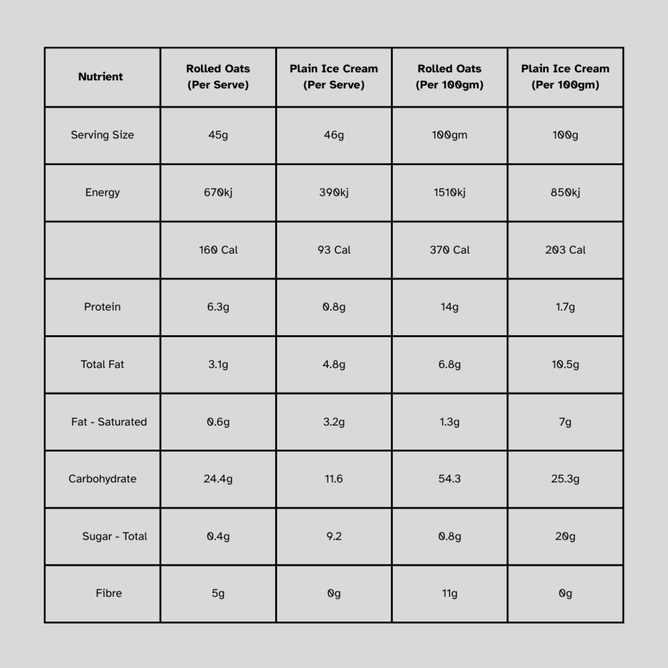

The Importance of Context: Oats vs. Ice Cream

Many people don't realise that total carbohydrates include starches, sugars, and fibre. This is why some nutrient-dense foods like oats can be higher in total carbs than a processed product, but the quality is vastly different.

Let's compare the nutrition labels per 100g for two common foods:

As you can see, oats have a much higher carbohydrate count, but the majority of those carbs come from complex starches and a high base of fibre. This slows down digestion and gives you a steady, sustained release of energy. The example ice cream here is a plain flavor, which on the other hand, has a lower total carbohydrate number, but almost all of it is pure sugar, which causes a sharp spike in blood sugar followed by a crash.

Total Carbohydrates: The "Carbohydrate" line on the label includes starches, fibre, and sugars.

What to Look For: Below the total carbohydrates, you will see the "Sugars" line. This includes both naturally occurring sugars (like those in fruit and milk) and added sugars.

The Strategy: Use the ingredient list to spot added sugars and sugar alcohols. A good rule of thumb is to choose products with less than 5g of total sugar per 100g. If a product has more, check the ingredients list to see if the sugar is coming from fruit (like raisins) or if it's from added sweeteners.

The Ingredient List

The ingredient list tells you exactly what is in the food, and it's your best tool for spotting hidden sugars, fats, and additives.

What to Look For: Ingredients are listed in descending order by weight. This means the first few ingredients make up the majority of the product.

The Trick: Look for different names for the same ingredient. For example, sugar can be listed as:

Sucrose

Glucose

Fructose

Maltodextrin

Corn syrup

Agave nectar

Honey

Dextrose

The Strategy: If you see any form of sugar listed among the first few ingredients, the product is likely not as healthy as its marketing claims.

Protein and Fibre Claims

Labels love to highlight "high protein" or "high fibre" to make products sound healthy. But these claims can be misleading.

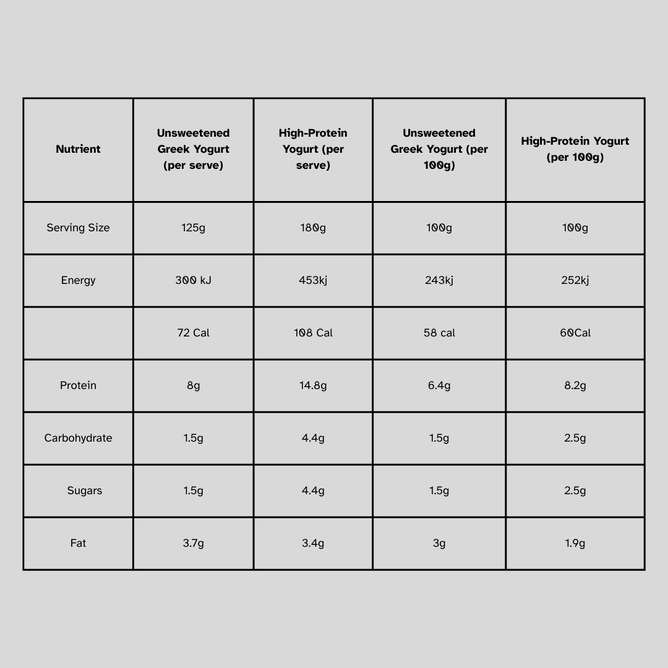

The Reality of "High Protein" Yogurt

A "high protein" yogurt, for instance, might be advertised as a superior choice, but the difference in nutritional value is often minimal compared to a standard, unsweetened Greek yogurt. Let's compare two hypothetical yogurts to see the reality behind the marketing claims.

As the table shows, the "high-protein" yogurt's serving size is 55gms larger, which is a common trick to make the "per serving" numbers look more impressive. When you compare them per 100g, the actual nutritional difference is minimal. This small difference can sometimes cost you an extra $2-$3 per tub, and it's not going to make a significant impact on your overall daily protein intake.

High Protein: According to New Zealand guidelines, a food can be called "high protein" if it contains at least 10g of protein per 100g (or 20g if it's a liquid).

High Fibre: A food can be called "high fibre" if it contains at least 6g of fibre per 100g (or 3g if it's a liquid).

The Strategy: Always compare similar products side-by-side using the "per 100g" column. This gives you an honest, apples-to-apples comparison and helps you determine if the extra cost is truly worth the minimal nutritional difference. It's also important to remember that just because a food doesn’t contain much protein doesn't mean you should avoid it. Vegetables, fruit, and nuts are lower in protein but are still highly nutritious and should be included in your diet.

Saturated Fat & Trans Fats

While not all fats are bad, saturated fats can be a concern for many people.

What to Look For: The "Fat, total" and "Fat, saturated" lines. Trans fats are not always required on a label, but you can sometimes spot them in the ingredient list as "partially hydrogenated vegetable oil."

The Strategy: Aim to keep your saturated fat intake low. A good rule of thumb is to choose products with less than 3g of saturated fat per 100g.

Sodium (Salt)

Sodium, a component of salt, is a critical part of your daily intake. Excessive sodium can be linked to high blood pressure and other health concerns.

What to Look For: The "Sodium" line on the NIP.

The Strategy: A good rule of thumb for most people is to aim for products with less than 120mg of sodium per 100g. Products with over 600mg per 100g are considered high in salt and should be limited. Your daily Suggested Dietary Target (STD) for sodium intake is approximately 2,000mg per day.

The Health Star Rating

Introduced in New Zealand in 2014, the Health Star Rating is a voluntary front-of-pack labelling system that rates the overall nutritional profile of a packaged food from 0.5 to 5 stars. The higher the stars, the healthier the product is considered to be.

What It's For: The system is designed to provide a quick, at-a-glance comparison between similar products. For example, it's a useful tool for comparing two different brands of breakfast cereal or two different types of milk.

The Trick: The system is flawed when you try to compare across food categories and in its "as prepared" calculation. For example, Nestlé came under fire for giving Milo a 4.5-star rating on the basis that it was prepared with skim milk. On its own, Milo earned just 1.5 stars. This "as prepared" loophole gives consumers a false sense of making a healthy choice.

The Strategy: The system is currently under review in New Zealand due to its "not fit for purpose" design. Use the Health Star Rating as a guide for comparing similar products, but don't rely on it alone. Always check the nutrition information panel and the ingredient list to make an informed choice.

Putting it All Together: A Quick Checklist

When you pick up a product, ask yourself these questions:

What is the serving size? Is it realistic for what I'm going to eat?

Is sugar listed in the first three ingredients?

How much sugar is there per 100g? (Aim for under 5g)

How much saturated fat is there per 100g? (Aim for under 3g)

How much sodium is there per 100g? (Aim for under 120mg)

Is the "high protein" or "high fibre" claim supported by the "per 100g" column?

What is the Health Star Rating? How does it compare to a similar product?

One of the first things clients tell me when they want to lose weight is, "I just don't know what to eat." But the truth is, most of the time it’s not about what we eat, but how much.

When you start to look at food as a "value for money" equation—considering serving size and total energy—you can start to make better choices. And the best way to do that is with a pair of kitchen scales. It can be a real shock to see what an actual serving looks like. Try weighing a 30g portion of corn chips (it's about 6 or 7 chips, by the way) or a 45g serving of ice cream. The foods you thought were good for you might be the reason you now need to pay attention to what you're consuming.

My advice to anyone learning to read a food label: get out your scales and weigh what you would normally eat. It's the most powerful first step you can take.